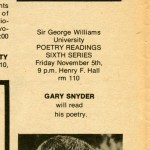

Gary Snyder reads from poems later collected in Turtle Island (New Directions, 1974). All poems read from Turtle Island were originally published in a limited edition book called Manzanita (Four Seasons Press, 1972). He also reads one poem from Regarding Wave (Fulcrum Press, 1971), one poem from Coyote’s Journal 9 (1971), and from Mountains and Rivers Without End only published in 1997 by Counterpoint, as well as several poems from unknown sources. Snyder reads one poem from The Fudo Trilogy (Shaman Drum, 1973). Gary Snyder states in his first introduction [02:58] that he will not read anything that is published, but these poems have almost all been published subsequently, after this reading.

Richard Sommer

00:00:17.61

Probably some of us are here in order to look at or touch the Gary Snyder who actually went and did all those semi-mythological things, who has climbed mountains and traveled in India with Allen Ginsberg, who provided Kerouac with a book character, who has lived in or on the edges of several different kinds of wilderness, who has lived in the precincts of Japanese Buddhist monasteries, who has fought, I think has fought hard, to keep other cultures than ours, and other kinds of life than human life, from obliteration. And who has written poems out of the consciousness of these things. For myself, Gary Snyder hasn't made poems so much as he has provided me with windows made out of words. These are windows that have had a way of, themselves disappearing, leaving me usually standing where I think I want to be, out in the open world. So, I came here, I've come here, to meet whoever it is that makes so many good windows. I'll let you discover for yourselves how much this window-maker is what a window-maker should be, himself, just open and clear. I'd like to present Gary Snyder.

Gary Snyder

00:02:58.55

[Aside] I forgot one more thing I wanted to have out here. Good evening. I'm going to read in two sets this evening, with a little intermission. And first of all, I'm not going to read any poems tonight from my published books, because those poems are available and what is interesting to me is always what I'm doing, where I'm moving. So I'm going to read from a cycle of short poems, moderately short poems, which I call "Charms," and then there'll be a break, and then I'm going to read recent sections that I've been working on from a long poem in progress called "Mountains and Rivers Without End." I came back to the United States from Japan with my wife and children about three years ago now, and went as rapidly as possible to settle in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, on the north slope of the south fork of the Yuba river at three-thousand foot elevation. And I've been living there for almost two years now. I'm saying this by way of introduction to this first cycle of poems called "Charms." I was brought up on a farm, and all of my ancestors that I know of, for the last few generations on both sides, were rural people, or miners, miners in Colorado, Leadville, places like that. And it amazes me in a mysterious way how to get back to doing what my father was doing when I was a little boy, and what, and which I remember as a little boy, and to get back to doing what my grandfather was doing, which is to say--again, looking at the fences, looking at the stumps, looking at the house, looking at the well, looking at the spring and saying, how are we going to do it--touches me more deeply than I can possibly explain. And at the same time, being confronted again with these choices, which are the choices of the American frontier, and also the choices of medieval Europeans, and neolithic Mediterranean people, and neolithic Japanese people, and neolithic Chinese people. With what I've come to understand, a little more now, about history, anthropology, and biology, I feel an extraordinary responsibility to understand why I make the choices I make, in such matters as, where does one break the ground and locate a garden, or which trees does one select to fall. In other words, I find myself again in that position of entering virgin land, and this time, I want to understand, in the process of making my own choices, I want to understand why we did it wrong, every time before, and hope to get some insights in how one goes about doing it right, this time. In moving toward that understanding, in making the choices that I have to make, about how we are going to live, in the semi-wilderness and true wilderness of the Sierra Nevada, my teachers have to be scientific foresters, biologists and ecologists on the one hand, and the American Indians on the other. There are no other teachers available for these choices.

Gary Snyder

Introduces poetry cycle “Charms”

00:08:02.72

And so these poems, in the cycle called "Charms," reflect those debts and reflect the search for that knowledge, insofar as I've gotten into it up to this point. It starts with a little chant, called "Grace for Love." Before we... grace, in the sense of the grace that we say before meals. Which is, grace is gratitude, an expression of gratitude for a meal. And the gratitude that we say at my rancheria is a kind of a rough translation from a Japanese Buddhist grace which goes like this in English: "We venerate the three treasures and are thankful for this meal, the work of other people, and the suffering of other forms of life." The need for grace, for love, is something I became aware of when I realized that there was a level of validity in the Catholic Church's objection to contraceptive devices, insofar as love, like food, is a sacrament, and that there is a level in which the act of love should inevitably be connected with the consciousness of its role in moving the seed, in transmitting the energy of the knowledge of the biomass, as transmitted down through time. But I felt that the Church is far too simple-minded in assuming that the energy aroused in the sacrament of love, in the direction of fertility, has to mean literally that the people who are acting that sacrament out have to necessarily procreate their own kind. And so we came to this, I and several other people, came to this, as what primitive people would call the transferral of merit, or species-increase ritual. In other words, we make love with gratitude to other beings, and wish to transfer our fertility from the human race to the vanishing species.

Annotation

00:11:09.69

Chants "Grace for Love"

Annotation

00:14:20.19

Reads "A Curse on the Man In the Pentagon, Washington"

Gary Snyder

00:16:37.00

That's from a Cheyenne ghost dance song, that little last chorus.

Annotation

00:16:43.10

Reads "I went into the Maverick Bar…"

Gary Snyder

00:18:25.99

The Navajo word "Anasazi" means "the ancient ones." It's the name that the Navajo gave to the people who lived in the canyons and cliffs of Chaco Canyon and Canyon De Chelly and Mesa Verde and many other sites. Probably the people were the ancestors of the present Pueblo people, living there probably up until the twelfth century, till the great drought of the thirteenth century. The people who more than any others, to judge from what the Pueblo people are still able to transmit today, the people who more than any others have achieved what could truly be called "civilization" on this continent, and whose lore embodies perhaps two millennia of deep experience. I wrote this at Canyon De Chelly.

Annotation

00:19:52.26

Reads “Anasazi”

Gary Snyder

00:21:11.48

The Canyon De Chelly, which will come up in another poem I'm going to read later today, and in fact, all over the West, all over the Great Basin, and in other parts of North America too, notably on the granite outcroppings on the northern shores of Lake Superior, for example, are designs pecked into the rocks, petroglyphs. Anthropologists, Americanists, whatever you call 'em, haven't had much time to study those petroglyphs yet, because they've been engaged through all the years of this century in a hasty, half-successful salvage operation. Salvaging the remnants of this or that dying culture, recording and taping the last words of a dying language, and they've had no time to give to studying these older things that they know are there, such as the petroglyphs. But the petroglyphs have a repeated vocabulary of motifs which are found in patterns distributed all over North America, and particularly in the West. One of the most widespread is a hand, that someone has put on a cliff or a boulder face, apparently outlined, and then filled it in with red, hematite, or a red hand. That red hand often is lacking a finger, or lacking a finger-joint. This would not be notable in itself if it weren't that in the caves of southern France and northern Spain, there are dated, back as far as 40,000 years, the same red hands, with missing fingers and missing finger-joints are found. This is only one of a number of things which are found all the way. And so this next poem, "The Way West Underground," is one of a number of poems, and this is perhaps the most intellectual of them, in which I'm trying to trace out how you get back to make the line of connection between what I know the American knows, what I am beginning to know the American Indian knew, and what I am beginning to know our prehistoric ancestors knew, which was not a different knowledge. And the question of why our prehistoric ancestors lost it is another question. Actually the main impetus of this poem deals with the bears, because there's an international mystery religion called the Bear Cult, that runs all the way from Finland to Utah, across Siberia, and it shares the mysterious central theme, which is a girl who marries a bear. I've written several poems about that girl. And about the bears. And so this is coming in on that from another angle.

Annotation

00:25:12.27

Reads "The Way West Underground."

Annotation

00:26:55.00

END OF RECORDING.

Link to Part 2 of recording.

Richard Sommer

00:00:17.61

Probably some of us are here in order to look at or touch the Gary Snyder who actually went and did all those semi-mythological things, who has climbed mountains and traveled in India with Allen Ginsberg, who provided Kerouac with a book character, who has lived in or on the edges of several different kinds of wilderness, who has lived in the precincts of Japanese Buddhist monasteries, who has fought, I think has fought hard, to keep other cultures than ours, and other kinds of life than human life, from obliteration. And who has written poems out of the consciousness of these things. For myself, Gary Snyder hasn't made poems so much as he has provided me with windows made out of words. These are windows that have had a way of, themselves disappearing, leaving me usually standing where I think I want to be, out in the open world. So, I came here, I've come here, to meet whoever it is that makes so many good windows. I'll let you discover for yourselves how much this window-maker is what a window-maker should be, himself, just open and clear. I'd like to present Gary Snyder.

Gary Snyder

General Introduction

00:02:58.55

[Aside] I forgot one more thing I wanted to have out here. Good evening. I'm going to read in two sets this evening, with a little intermission. And first of all, I'm not going to read any poems tonight from my published books, because those poems are available and what is interesting to me is always what I'm doing, where I'm moving. So I'm going to read from a cycle of short poems, moderately short poems, which I call "Charms," and then there'll be a break, and then I'm going to read recent sections that I've been working on from a long poem in progress called "Mountains and Rivers Without End." I came back to the United States from Japan with my wife and children about three years ago now, and went as rapidly as possible to settle in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, on the north slope of the south fork of the Yuba river at three-thousand foot elevation. And I've been living there for almost two years now. I'm saying this by way of introduction to this first cycle of poems called "Charms." I was brought up on a farm, and all of my ancestors that I know of, for the last few generations on both sides, were rural people, or miners, miners in Colorado, Leadville, places like that. And it amazes me in a mysterious way how to get back to doing what my father was doing when I was a little boy, and what, and which I remember as a little boy, and to get back to doing what my grandfather was doing, which is to say--again, looking at the fences, looking at the stumps, looking at the house, looking at the well, looking at the spring and saying, how are we going to do it--touches me more deeply than I can possibly explain. And at the same time, being confronted again with these choices, which are the choices of the American frontier, and also the choices of medieval Europeans, and neolithic Mediterranean people, and neolithic Japanese people, and neolithic Chinese people. With what I've come to understand, a little more now, about history, anthropology, and biology, I feel an extraordinary responsibility to understand why I make the choices I make, in such matters as, where does one break the ground and locate a garden, or which trees does one select to fall. In other words, I find myself again in that position of entering virgin land, and this time, I want to understand, in the process of making my own choices, I want to understand why we did it wrong, every time before, and hope to get some insights in how one goes about doing it right, this time. In moving toward that understanding, in making the choices that I have to make, about how we are going to live, in the semi-wilderness and true wilderness of the Sierra Nevada, my teachers have to be scientific foresters, biologists and ecologists on the one hand, and the American Indians on the other. There are no other teachers available for these choices.

Gary Snyder

00:08:02.72

And so these poems, in the cycle called "Charms," reflect those debts and reflect the search for that knowledge, insofar as I've gotten into it up to this point. It starts with a little chant, called "Grace for Love." Before we... grace, in the sense of the grace that we say before meals. Which is, grace is gratitude, an expression of gratitude for a meal. And the gratitude that we say at my rancheria is a kind of a rough translation from a Japanese Buddhist grace which goes like this in English: "We venerate the three treasures and are thankful for this meal, the work of other people, and the suffering of other forms of life."The need for grace, for love, is something I became aware of when I realized that there was a level of validity in the Catholic Church's objection to contraceptive devices, insofar as love, like food, is a sacrament, and that there is a level in which the act of love should inevitably be connected with the consciousness of its role in moving the seed, in transmitting the energy of the knowledge of the biomass, as transmitted down through time. But I felt that the Church is far too simple-minded in assuming that the energy aroused in the sacrament of love, in the direction of fertility, has to mean literally that the people who are acting that sacrament out have to necessarily procreate their own kind. And so we came to this, I and several other people, came to this, as what primitive people would call the transferral of merit, or species-increase ritual. In other words, we make love with gratitude to other beings, and wish to transfer our fertility from the human race to the vanishing species.

Annotation

00:11:09.69

Chants "Grace for Love"

Annotation

00:14:20.19

Reads "A Curse on the Man In the Pentagon, Washington"

Gary Snyder

00:16:37.00

That's from a Cheyenne ghost dance song, that little last chorus.

Annotation

00:16:43.10

Reads "I went into the Maverick Bar…"

Gary Snyder

00:18:25.99The Navajo word "Anasazi" means "the ancient ones." It's the name that the Navajo gave to the people who lived in the canyons and cliffs of Chaco Canyon and Canyon De Chelly and Mesa Verde and many other sites. Probably the people were the ancestors of the present Pueblo people, living there probably up until the twelfth century, till the great drought of the thirteenth century. The people who more than any others, to judge from what the Pueblo people are still able to transmit today, the people who more than any others have achieved what could truly be called "civilization" on this continent, and whose lore embodies perhaps two millennia of deep experience. I wrote this at Canyon De Chelly.

Annotation

00:19:52.26

Reads “Anasazi”

Gary Snyder

00:21:11.48

The Canyon De Chelly, which will come up in another poem I'm going to read later today, and in fact, all over the West, all over the Great Basin, and in other parts of North America too, notably on the granite outcroppings on the northern shores of Lake Superior, for example, are designs pecked into the rocks, petroglyphs. Anthropologists, Americanists, whatever you call 'em, haven't had much time to study those petroglyphs yet, because they've been engaged through all the years of this century in a hasty, half-successful salvage operation. Salvaging the remnants of this or that dying culture, recording and taping the last words of a dying language, and they've had no time to give to studying these older things that they know are there, such as the petroglyphs. But the petroglyphs have a repeated vocabulary of motifs which are found in patterns distributed all over North America, and particularly in the West. One of the most widespread is a hand, that someone has put on a cliff or a boulder face, apparently outlined, and then filled it in with red, hematite, or a red hand. That red hand often is lacking a finger, or lacking a finger-joint. This would not be notable in itself if it weren't that in the caves of southern France and northern Spain, there are dated, back as far as 40,000 years, the same red hands, with missing fingers and missing finger-joints are found. This is only one of a number of things which are found all the way. And so this next poem, "The Way West Underground," is one of a number of poems, and this is perhaps the most intellectual of them, in which I'm trying to trace out how you get back to make the line of connection between what I know the American knows, what I am beginning to know the American Indian knew, and what I am beginning to know our prehistoric ancestors knew, which was not a different knowledge. And the question of why our prehistoric ancestors lost it is another question. Actually the main impetus of this poem deals with the bears, because there's an international mystery religion called the Bear Cult, that runs all the way from Finland to Utah, across Siberia, and it shares the mysterious central theme, which is a girl who marries a bear. I've written several poems about that girl. And about the bears. And so this is coming in on that from another angle.

Annotation

00:25:12.27

Reads "The Way West Underground."

Annotation

00:26:55.00

AUDIO RECORING ENDS.

Link to Part 3 of recording.

Gary Snyder

00:00:02.00

Everything in this next poem is all true. Almost everything.

Annotation

00:00:17.76

Reads "The Call of the Wild," Part I

Annotation

00:00:32.51

Reads "The Call of the Wild," Part II

Annotation

00:01:52.06

Reads "The Call of the Wild," Part III

Annotation

00:04:11.29

Reads "Source"

Gary Snyder

00:05:40.09

Introduces “Charms”

In the poem "Charms," which is dedicated to Michael McClure, who has more than any other living poet, or person even that I know, has gone farther than anyone else, I think, into becoming one with, in understanding, in penetrating, in perceiving the consciousness of other beings.

Gary Snyder

00:06:15.97

Reads "Charms"

Annotation

00:07:45.27

Loud applause follows this reading.

Gary Snyder

00:08:01.66

I want to read one little poem that kind of, that I just wrote on the plane the other day. Flying in here yesterday I wrote this. And then we'll take a break. But this belongs, really, with these poems.

Annotation

00:08:15.03

Reads "How did a great red-tailed Hawk come to lie on the shoulder of Interstate 5"

Gary Snyder

00:09:55.44

Okay, let's take a break. [Applause]

Audience Member 1

00:10:29.43

[Voice off-mike, crowd noise in background] Do you remember getting tiny toys for your children from San Francisco? There was a small book that I saw in the States, folded out in a certain, section-by-section, parts of the earth kinda, growing larger and larger and larger...

Gary Snyder

00:10:46.02

I haven't seen it.

Audience Member 1

00:10:48.01

No, I guess...it's sort of, um, anti-war toys

Gary Snyder

00:10:51.22

Sounds nice. Yeah. Some place in San Francisco you can get it?

Audience Member 1

00:10:56.10

Um, I don't know, it was from a certain, a certain group of people, and I don't remember their names. It was beautiful. Nice gift to give little kids.

Gary Snyder

00:11:07.81

I shall watch for it when I go there again. Thank you.

Audience Member 1

00:11:13.39

Okay. You bet. [Inaudible]

Gary Snyder

00:11:14.19

Okay [Laughs.]

Audience Member 2

00:11:19.67

Man you're incredible. You're so good. I really dig your stuff.

Gary Snyder

00:11:26.33

[Laughs] Thank you.

Audience Member 2

00:11:26.92

I really dig it, will you come for a drink with me later? With me and my friends?

Gary Snyder

00:11:31.38

I gotta go some place later.

Audience Member 2

00:11:33.85

You sure?

Gary Snyder

00:11:34.65

Yeah. I mean, like I...they got something set up for me.

Audience Member 2

00:11:38.15

I don't, I don't know, I really dig that, I really dig that [inaudible] I just came in, I thought your stuff was so incredible....Your stuff, the way you bring it across to people!

Gary Snyder

00:11:51.21

Well, that's what I try to do.

Audience Member 2

00:11:54.07

Have you written a book?

Gary Snyder

00:11:54.68

I've written a lot of books. [Laughs]

Audience Member 2

00:11:58.41

No no no, no really, no really, I don't know too much about...Gary Snyder, you know?

Gary Snyder

00:12:04.00

Well, you'd probably find, I don't know, because I'm coming here, because of my being here now, they've probably got some of my books in the bookstore, if you want to go look. [Laughs]

Audience Member 2

00:12:13.56

See I'm writing this play right now, you know? I'm trying to express myself and it's really...it's really strange--[Cut]

Annotation

00:12:21.26

Audible edit made to tape; recording continues presumably following the session break; unknown interval elapsed.

Gary Snyder

00:12:21.29

Well, there has been a great deal of opposition to nuclear energy, and nuclear power-generating stations, in the United States so effective in some areas that a lot of generating plants have been blocked or slowed down in their construction. And I think that the United States government is about to launch on an enormous effort to calm the public and to lull it into accepting massive developments of nuclear energy generating centers, fast-breeder and later, perhaps, fusion. Now I myself would have no objection to such a thing if I could be convinced that it was safe, both in the long term and the short term, and although it might be conceivably safe in the short term, I can see no way in which it would be safe in the long run, because nuclear wastes accumulated over, say, several centuries, as they might be, or more, in increasing quantities around the globe, are going to out eventually, and even though you can say, well, we're putting it off for five hundred thousand years, five hundred thousand years is not a very long time. And if we are feeding a wasteful, industrial, technological, consumer society for a few more centuries, buying it a few more centuries of life, at the expense of all future biological health on the planet, it's obviously not worth it. The Amchitka test, which is possibly interested in such things as what uses very large explosions would have in releasing oil from oil-bearing shale or something like that, I think the U.S. administration is going ahead with this test in the face of all this criticism, deliberately, as a deliberate and very intelligent gamble. The chances are that nothing will happen. When nothing happens, then they will be able to say, "All you people were hysterical. You see? Nothing happened." And that will buy them a lot of time and a lot of credibility to proceed strongly and forcibly with more nuclear testing and more nuclear power generation development. And the conservationists, perhaps, have in a way, played into their hands, by making such a big issue out of it, so that they will be left holding an empty bag if nothing happens. If something does happen, then the administration can say, "You're right, we were wrong," and Nixon perhaps forfeits the next election. That's all. Okay.

Gary Snyder

Introduces “Mountains and Rivers Without End”

00:15:25.61

"Mountains and Rivers Without End" is a poem that I've been working on, it's a long poem, a long series of inter-connected long poems that I've been working on for some years. I'm going to read several sections from that tonight. Including one or two that are very recent, in fact these are all pretty recent. "Mountains and Rivers without End." The title of the poem comes from a Yuan Dynasty Chinese scroll, that unfolds sideways and is thirty-five feet long. By way of introduction, a little poem called "The Rabbit." There are many sections to this, I'm only going to read [counts under breath.]..six tonight.

Annotation

00:16:27.56

Reads "The Rabbit"

Gary Snyder

00:18:04.22

"The California Water Plan." The state of California at the moment is engaged in a large, incredibly wasteful, incredibly stupid, illegal, even by their own terms, water plan project, which if they're lucky, will salinate the Sacramento Valley and make agriculture permanently impossible. I was up in the Minarets in the Sierra last summer, thinking about the California Water Plan, and I perceived something of what the true California Water Plan was. So I wrote this down. It refers to an obscure little Buddhist god called Fudo, or Achala, who is my particular guardian, my persona guardian and my personal teacher, and, so I use, I refer to him, in several poems. The other two poems in which I refer to him actually are a piece called "Smokey the Bear Sutra," and another piece called "Spel Against Demons." This is the final, actually, this is the third and final poem in the trilogy of Fudo poems. Also. But you'll find all about Fudo in this poem, it'll drive you crazy.

Annotation

00:19:48.11

Reads "The California Water Plan"

Gary Snyder

00:25:34.22

"Kumarajiva's Mother." Now, the rest of these poems that I'm going to read this evening are cutting back and forth between ancient India and ancient North America. I--living as I do and where I have lived all my life, we face the Pacific. And, the American Indian came from Asia, or vice versa, the Asians came from North America. I mean I know a Shoshone who says that. He says, "We've always been here, those Asians came from here." [Laughter.] "What do you mean we came from someplace else, that's some white anthropologist theory." [Laughs] "Kumarajiva's Mother." Kumarajiva was a great Buddhist monk-scholar-translator, who was kidnapped by the Chinese from Central Asia, by force, and carried off to China where he was made to translate Sanskrit Buddhist texts into Chinese, and he stayed there the rest of his life, with a crew of about eighty Chinese assistants, day and night, translating sutras. He did a lot of translation. He also got in trouble, because he liked girls, and on one occasion, because he actually had mistresses apparently, he ate a bowl of needles, like you sew with needles, in front of an assembly of all the monks and assistants in Peking, or no it wasn't Peking in those days, it was Chang'an, all of the monks and assistants in the capital, Chang'an, and then he said, "When you boys can eat needles, you can have girlfriends too." [Laughter] But this poem is about his mother. And I really, I mean I could explain to you why I wrote this poem but it isn't really worth explaining, I'll just read it. It has to do partly with the fact that my mother has freckles. And I was trying to figure out at this time, when I wrote this, I was trying to figure out whatever happened to women in Buddhism? Like something happened to 'em. They got lost. For a long time, anyway.

Annotation

00:28:22.08

Reads "Kumarajiva's Mother"

Annotation

00:30:59.77

AUDIO RECORDING ENDS.

Link to Part 4 of recording.

Gary Snyder

00:00:00.00

[Inaudible.]..alone in the 8th century, and studied at an enormous Buddhist, Mahayana university called NAllenda, for fifteen years, and then walked back to China, with a fraying pack full of books, which he translated for the next twenty years after he got back to China. He brought the school of Buddhism, which is called the school of Mind Only, and the school of Emptiness. That's one aspect of this next poem. Another aspect is a little petroglyph, American Indian petroglyph figure, called the hump-backed flute player, a little stick figure playing the flute, with a pack on his back, walking. He was found pecked on the rocks from Sonora, Mexico up into the Great Basin, and about which almost nothing is known. The Ghost Dance, which was a Messianic Indian religion, started by a Paiute named Wovoka, which asserted that perhaps by magic the white man could be swept away from North America and the game would return. And finally, the oldest living beings are the bristle-coned pine, who live in the White Mountains, at an elevation of nine thousand feet in eastern California, the oldest of which is something like four thousand five hundred years old. So this poem is called "The Humpbacked Flute Player."

Annotation

00:01:59.48

Reads "The Humpbacked Flute Player"

Gary Snyder

00:08:36.16

I'm going to finish with one more poem called "Down." These poems are not in the order that they're going to be, but they're in a convenient order for the moment.

Annotation

00:09:05.09

Reads "Down."

Annotation

00:11:48.46

Loud applause concludes reading.

Introducer

00:12:18.68

I can't thank you for that. I don't know any way. Charles Simic will be reading on November 19th. Thank you. [Applause]

Annotation

00:12:45.00

AUDIO RECORDING ENDS.

References

Boxer, Avi; Bryan McCarthy and Graham Seal. “re: Reverend Richard J. Sommer”. The Georgian [Sir George Williams University, Montreal.] November 12, 1971. Letters: page 4. ---.

“Get Your Shit Together...”. The Georgian [Sir George Williams University, Montreal.] November 19, 1971. Letters: page 4.

DiFranco, Aaron K. "Snyder, Gary". The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature. Jay Parini (ed). Oxford University Press 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Concordia University Library, Montreal. November 11, 2009. <http://0www.oxfordreference.com.mercury.concordia.ca/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t197.e0267>.

Maxwell, Glyn."Snyder, Gary". The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Poetry in English. Ian Hamilton (ed). Oxford University Press, 1996. Oxford Reference Online. Concordia University Library, Montreal. November 11, 2009. <http://0-www.oxfordreference.com.mercury.concordia.ca/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t58.e1130>.

Morrissey, Stephen. “Inexcusable Ignorance”. The Georgian [Sir George Williams University, Montreal.] November 26, 1971. Letters, page 4. Pearson, Allen. “The Second Coming?”. The Georgian [Sir George Williams University, Montreal.] November 12, 1971.

Letters, page 4. Snyder, Gary. The Fudo Trilogy. Berkley, California: Shaman Drum, 1973. ---.

Mountains and Rivers Without End. Washington, D.C.: Counterpoint Press, 1996. ---.

Regarding Wave. New York: New Directions Press, 1967. ---.

Six Sections from Mountains and Rivers Without End. San Francisco: Four Seasons Press, 1965. ---.

Turtle Island. New York: New Directions Press, 1969.

"Snyder, Gary". The Concise Oxford Companion to American Literature. James D. Hart (ed). Oxford University Press, 1986. Oxford Reference Online. Concordia University Library, Montreal. November 11, 2009. <http://0-www.oxfordreference.com.mercury.concordia.ca/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t53.e1832>.

"Snyder, Gary [Sherman]". The Oxford Companion to American Literature. James D. Hart (ed.), Phillip W. Leininger (rev). Oxford University Press 1995.

Oxford Reference Online. Concordia University Library, Montreal. November 11, 2009. <http:/0-www.oxfordreference.com.mercury.concordia.ca/views/ENTRY.html? subview=Main&entry=t123.e4461>.

Transcript and part of print catalogue by: Rachel Kyne Print Catalogue, “Introduction”, Research and Edits by Celyn Harding-Jones