In this blog post I wanted to make a few notes about the topic of “what do we look at while we listen?”. I’ve touched briefly on this topic in a previous post, but I find it to be such fascinating topic that I’ve got more to say.

Part of what fascinates me about the topic is that it can be approached from variety of perspectives: philosophical, aesthetic, psychological or cognitive, and others as well, I’m sure. A couple questions to help illustrate the point:

Philosophical and aesthetic:

- What kind of imagery (e.g. pictures, movie, etc.) would suit or even enhance the aesthetic of the audio?

- Do we need to (and should we?) supplement aural playback of spoken word or musical performances with visual imagery or can the audio stand alone as “good enough”?

- Does the addition of visual art to aural art detract from the aesthetic experience of the latter?

Psychological or cognitive:

- What types of visual information would help us to better process, synthesize, or internalize the information or artistic performance represented in audio form? For example, synchronized or tethered transcriptions of the audio and text of a poetry reading could be seen to be helpful in this way. Something like this has clear value in language learning and it seems like that value could extend to more sophisticated uses of language such as poetry analysis and research.

- Another example: does a waveform or some other visual representation of the audio content help us to navigate, understand, or process the audio material? Can too much visual information detract from or inhibit audio processing?

A few examples from existing software:

- DJ software (Traktor Scratch Pro, Serato Scratch Live, et cetera).

DJ’s frequently synchronize two or more tracks at a time (called mixing) which involves, among other things, matching the tempos and phases of multiple tracks. To do this, DJ’s typically listen for some pronounced element of a track (usually the bass drum) and use that as an indication of the tempo. They adjust the tempo of one track to match the other by listening to the bass drums, and make changes until they are synchronized. Up until recently this was a completely aural skill. New developments in software technology have made it possible to provide visual information to make this process easier. So, for example, colour-coded waveform displays help to differentiate the different parts of a track. Seeing two colour-coded waveforms side by side provides visual information that can make it easier to synchronize the two tracks than if you were using the aural information alone. Here is a picture of a waveform represented in Traktor Scratch Pro. Note the lighter colours represent lower frequencies in the audio (e.g. bass drum) and the darker colours represent higher frequencies in the audio (e.g. hi-hats or snare drum hits).

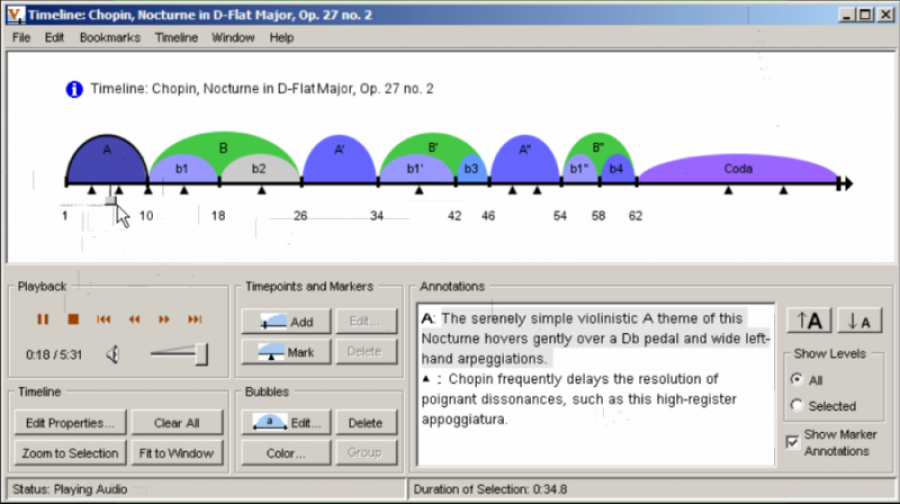

- Musical analysis software (e.g. Variations Timeliner).

Music students frequently need to analyze the different sections of a piece of music. The Variations Timeliner software makes it possible for music professors to divide up the audio timeline of a piece through colour-coded sections, with time-stamped annotations that display only at the appropriate points during playback. It seems that something like this might be applicable to poetry analysis.

- Web-based music distribution platforms (e.g. SoundCloud).

SoundCloud is one of the first (if not the first) web-based music distribution web site to have incorporated a waveform display into their media player. While waveform displays have been used in digital audio workstation (DAW) software for a long time, this feature has only recently been incorporated into web-based media players. Displaying the waveform is useful because it helps the listener/viewer to identify different sections of an audio track. For example, in the following waveform display, narrow bands typically represent breaks or pauses in between readings of separate poems, whereas thicker and continuous bands represent a single poem.

Finally, it is also interesting to consider the effect of popular video sites such as YouTube and Vimeo on the use of audio on the web. Most “audio” tracks posted on these sites (e.g., music) tends to include some form of visual information to accompany the audio (e.g. a static image or a series of images, a homemade music video, etc.). And according to a recent study by Cisco, “Peer-to-peer has been surpassed by online video as the largest category [of internet traffic].” It seems reasonable to predict, then, that web-based audio will continue to be increasingly paired with some form of visual information and will decreasingly appear as a stand-alone entity.