I’m in the process of compiling a list of digital tools that are useful for web-based poetry archives. I’m modelling the design on the Oral Historian’s Digital Toolbox. As I’ve been looking around I’ve come across a few things that have made me think about the relevance of location or geography to poetry. For example, I’ve just discovered the site Broadcastr which features the tagline: What’s your story?

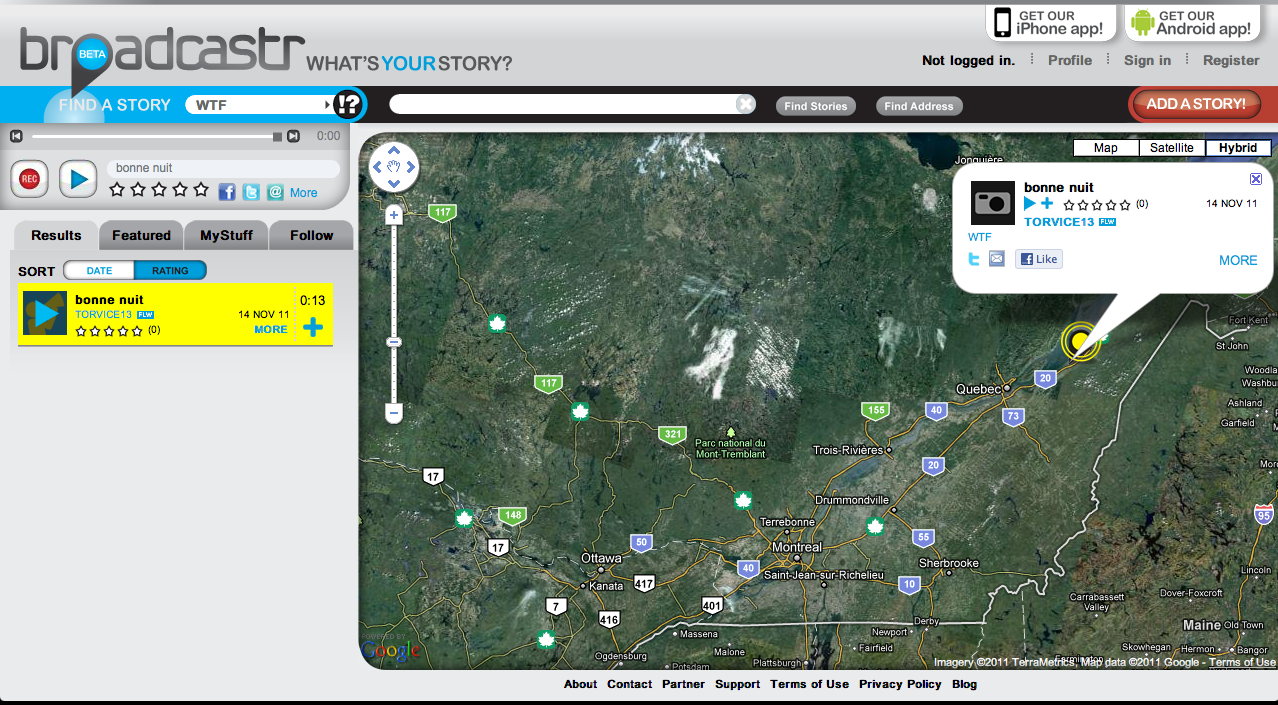

“Broadcastr is a Social Media platform for location-based stories. It enables the recording, indexing, listening, and sharing of audio content. Users can take a GPS-enabled walk as stories about their surroundings stream into their headphones, like a museum tour of the entire world.” (source) The site allows users to record stories by using either the Broadcastr website or through their mobile apps for iPhone or Android. For playback on the Broadcastr website, the stories can be searched by category (e.g. Arts & Culture, Citizen Journalism, History, Sound, Politics, WTF) or by location, using the markers on the Google Map which is central to the site’s interface. For playback on a mobile device, users can let their location determine what they hear.

Since the site doesn’t include much poetry, it likely to be of more interest to oral historians than poets. For example, the Centre for the Study of Folklore and Oral History at the University of Maine is using the site to distribute their recordings. But it does make me wonder if using location as an organizing principle for browsing could be useful to some poetry collections, and whether or not that view or perspective could be relevant to the SpokenWeb project. Some possible ideas include using the location where the recording took place, the birth place of the author, or places mentioned in a poem and integrating them with some kind of GIS display to facilitate both discovery of recordings and improved understanding of particular poetic works.

Related to that question is an article that I came across in the Poetess Archive Journal:

GIS, Texts, and Images: New Approaches

Ian Gregory, David Cooper

Abstract

“In this talk, given at the Digital Humanities Conference 2010, I describe work done in mapping two journals kept by two eighteenth-century poets as they toured the Lake District: Thomas Gray and Samuel Taylor Coleridge–the latter a Romantic writer. This work, as well as work done analysing place names and collocated words in the Lancaster Newsbook Corpus in order to determine which place names were associated with terms of war and which with monetary terms. The work we have done suggests that GIS can aid literary studies as a tool for both close and distant reading.”

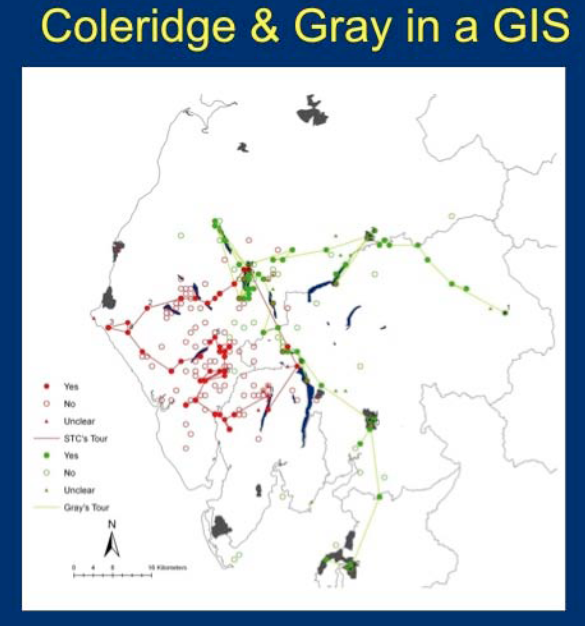

They coded the two writers’ journals in XML, marking up locations and distinguishing between places visited by the author versus those that were simply mentioned. “Having done this, extracting the place names from the text and reading them into a database table is a simple process. To convert this into a GIS the essential next stage is to give a coordinate to every place-name. This can be done by using a relational join to link the raw place-names to a place-name gazetteer, effectively a database table that gives a coordinate for every name.” Once they added the place names from the text into the GIS it allowed them to display the information in a variety of different ways. For example, the first screenshot shows a map of the routes that both writers took as well as places they mentioned along the way.

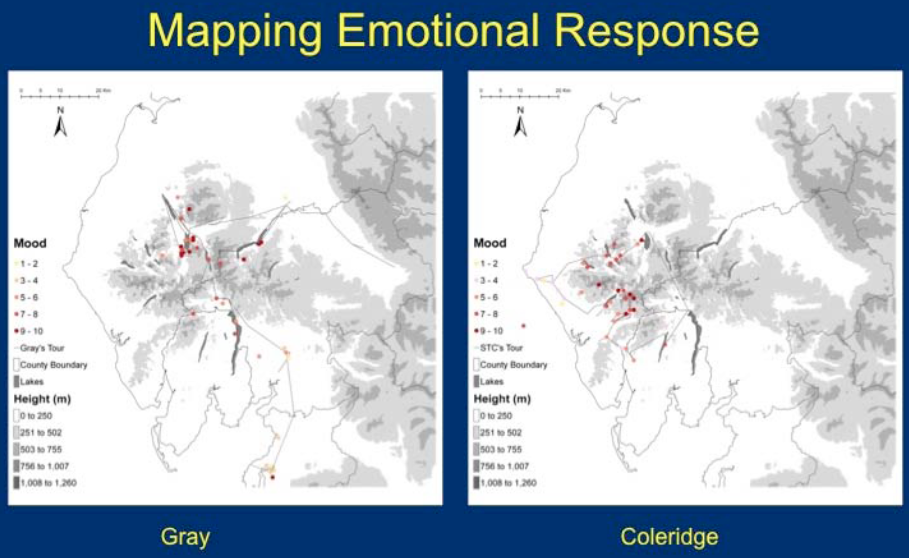

They also mapped out emotional responses of the writers’ tours by linking adjectives of varying strengths to particular locations. For example, the words “dull” and “tedious” would score as a zero whereas words like “sublime” and “terrifying” would score as a ten. For Gray, the “emotional centre” of his tour was Borrowdale and for Coleridge it was Sca Fell.

The authors also describe other applications of this text-born GIS data, such as integration with Google Earth and Flickr, among other things. Regarding the question of what GIS integration offers to literary research, they conclude that “mapping place-names provides a useful scholarly tool to help the researcher to understand these texts” and that GIS tools help “the reader understand the complex geographies within the texts under study”.